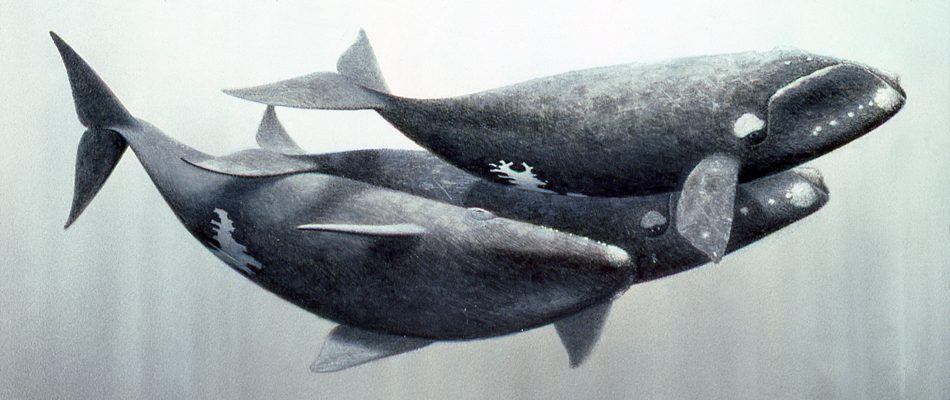

RIGHT WHALES

BALAENIDAE

Right whales were once numerous, but because they are big, slow, extremely fat, and they float when they are killed, their numbers were severely reduced during the heyday of hand-harpoon whaling. Their worldwide populations have yet to recover, and they remain extremely rare throughout most of their former range. Modern whalers have never found enough of them to warrant a serious pursuit, but they have been caught from time to time in the twentieth century.

Next to grubbing about on the sea floor for food like the gray whale, the simplest way for a baleen whale to make its living is to open its mouth and swim through dense concentrations of plankton. This is the manner in which t he right whales feed. Accordingly, their mouths, which remain open almost continuously as they skim through patches of plankton soup, have become enormous in the course of evolution, with tremendous surface areas of filtering baleen. Right whales can filter about 20 cubic yards (15 cubic meters) of water per minute, straining out the minute plankton prey species by the bushel and washing them down their gullets. A right whale’s feeding sounds include what might be called a loud smacking of the lips as the baleen plates are shaken to dislodge the plankton from the hairlike fringe of the plates before swallowing. This sound, which can be heard for considerable distances in air and underwater, was dubbed “baleen rattle” by the scientists who first noted it.

There are three basic types of right whales extant. The bowhead, or Greenland right whale, evolved its lifestyle to live in icy polar waters of the Northern Hemisphere, where plankton soup flourishes in summer months as the ice retreats. Although its population was decimated by Yankee whalers during the nineteenth century, the bowhead still survives, and is currently taken in small numbers in a subsistence harvest by Arctic Eskimos.

The right whale is thought by some researchers to comprise two distinct species virtually undistinguishable from each other in appearance. One is indigenous to the Northern Hemisphere and the other to southern oceans. The right whales of each hemisphere migrate to high latitudes to feed, then return to temperate or tropical sea to breed and calve. A single population of at least 1,000 individuals wintering along the Argentine coast seems to be thriving, but even that group is just a remnant of its former abundant South Atlantic stock. Another population of perhaps fewer than 200 individuals winters along the coast of Georgia in the United States and summers in the waters off New England. It has not grown perceptibly in numbers, but researchers have noted a few new calves in recent years. Some researchers believe that a factor in the right whale’s slow recovery from whaling is that the sei whales, which also possess fine baleen fringes and have a propensity for skimming plankton, may be competing for their feeding niche.

The third right whale is a pygmy version. Small, shy, and restricted to the Southern Hemisphere, it has never been hunted extensively, and its apparent lack of abundance seems to be due to its extreme evolutionary specialization rather than to overexploitation. There doesn’t seem to be an ecological place for a diminutive cetacean skim-feeder of copepods. Some authors place the pygmy right whale in its own family: Neobalaenidae (Gray, 1847), but a monotypic family so closely related to the other right whales serves no useful taxonomic purpose, and is generally not used.