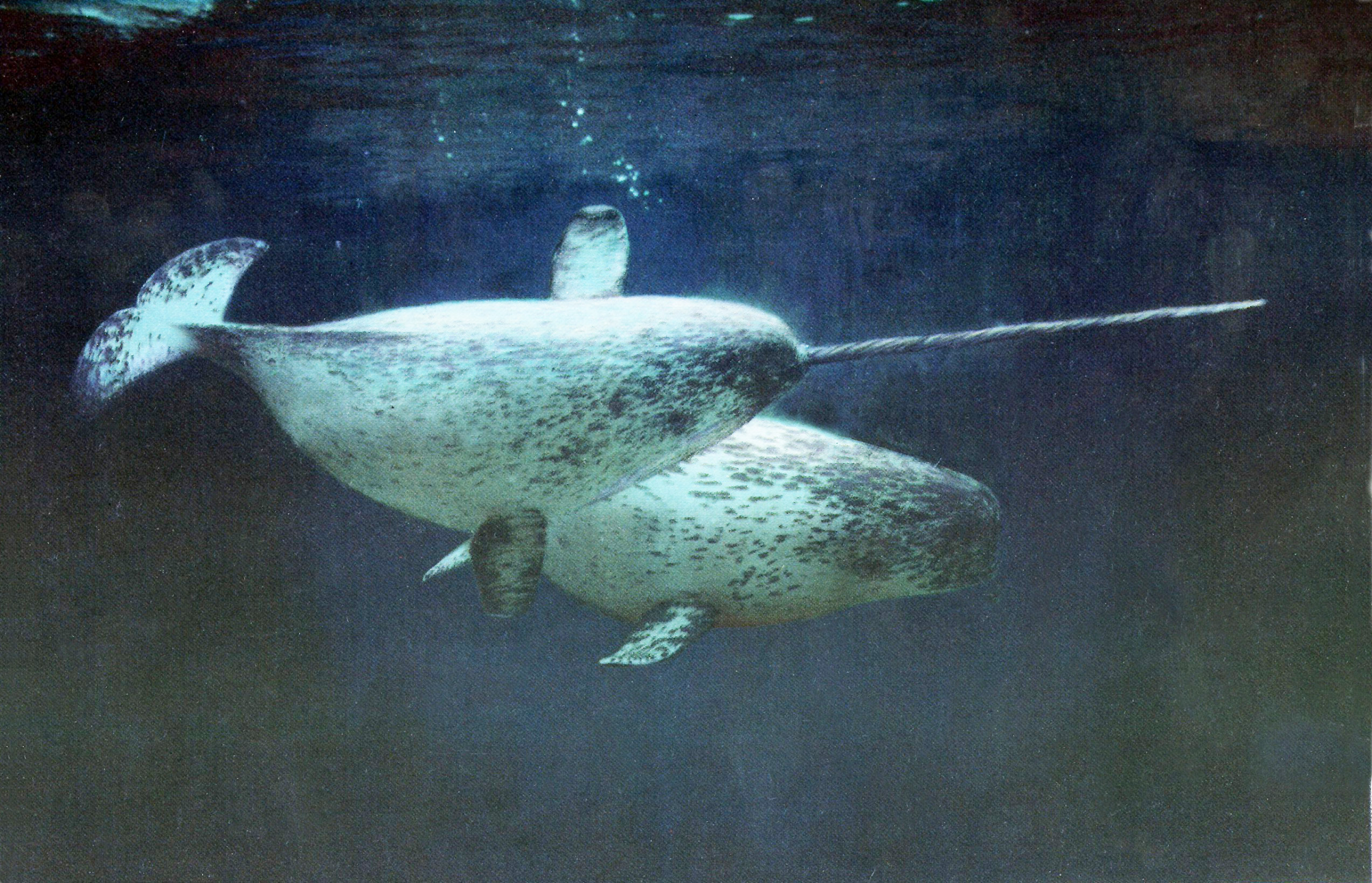

BELUGA and NARWHAL

MONODONTIDAE

Monodontidae Introduction

Apparently, at some time in the evolution of dolphin-like creatures, some animals were trapped in an arctic environment by shifting patterns of ice and climate, and there they evolved successfully over the eons into the narwhal and beluga whales we know today. Both animals have retained freedom of movement in their neck vertebrae, lost their dorsal fins, developed thick layers of insulating blubber, and have adapted to spend their entire life cycles close to the advancing and retreating ice pack of the Northern Hemisphere. Both are gregarious animals, and both are oddities that have stirred the mythic imaginations of peoples over many centuries.

Medieval Europeans ascribed the long slender spiral tusk of the narwhal to the mythical beast they called the unicorn. Their tusks brought princely praise and reward to venturesome men who brought them back from the early voyages of northern exploration. Everywhere they were objects of curiosity. Today we know where the tusks originate, but they still pose questions. Of what use is the tusk to the narwhal? Why does it erupt through the gum only in the males? And why only the left one of a pair? Why does it always spiral toward the left?

The beluga has no tusk, but its vociferous squeals and chirps, emitted as it travels along the ice floes, often assembling in large herds to feed, have earned it the name “sea canary”. People walking on the ice or drifting in a boat near a group of belugas hear a constant chorus of their canary-like songs.

Resembling a small beluga are the Irrawaddy and Australian snub-fin dolphins. Although these animals are currently placed in the family Delphinidae, their anatomical similarities to the beluga have given rise to a movement to place them in the family Monodontidae with the beluga and narwhal, despite their tropical distribution.